Planters Hotel

Planter's Hotel (first) - On Second Street. Opened 1817.

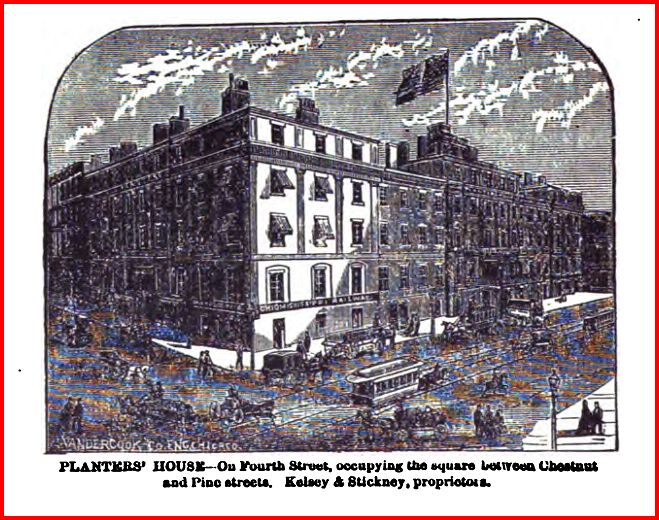

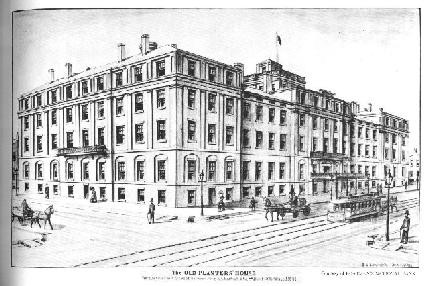

Planter's Hotel (second) - At Fourth and Pine. Ground was broken in March, 1837, completed March, 1841. Destroyed 1891.

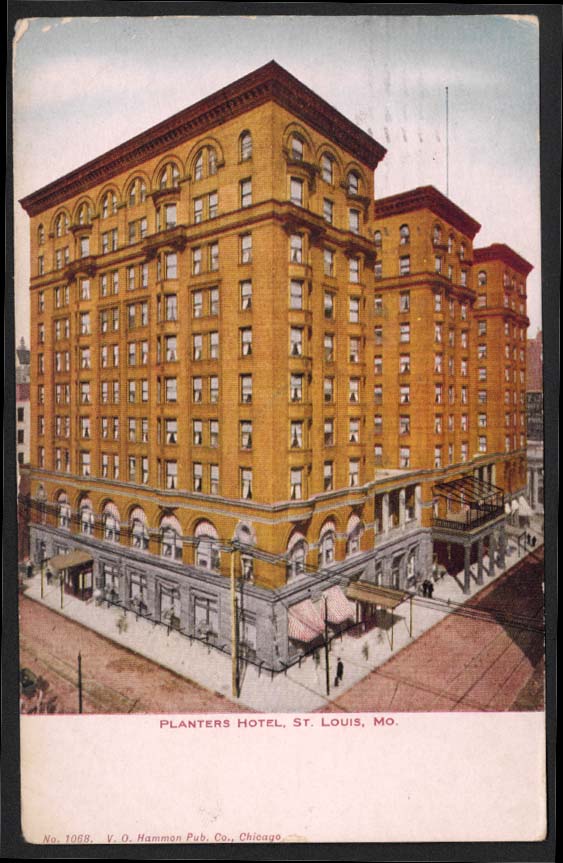

Planter House Hotel (third one) (now the site of Boatmen's Tower) Completed 1891, destroyed 1976

Planter's Hotel image published in 1858

Planter's Hotel image published in 1858

The third Planter's Hotel

The third Planter's Hotel

The following announcement, made upon the eve of its opening, will explain why an intended compliment was not conferred: "We would briefly observe, further, that the title of the house is that given in the charter. After the house had been taken by the present enterprising proprietors, Messrs. Stickney & McKnight, and after they had ordered their furniture, part of which, the porcelain, cutlery, etc., was manufactured in England, and the name of the establishment impressed or otherwise fixed on every piece, the board of managers altered the title to that of The Lucas House, in honor of the liberal patron of the same, the Hon. Judge Lucas, but on account of the above previous arrangement of the proprietors they have felt themselves bound to open under the title of The Planters House. "On the 1st of April, 1841, the hotel went into operation. Stickney & McKnight, the lessees, had previously conducted the National Hotel, and were experienced hotel-keepers. Mr. Stickney subsequently bought out Mr. McKnights interest, and afterwards associated with him Leonard Scolly. The latter died in the fall of 1860, and Mr. Stickney kept the house until April, 1864, when he retired with a competency. Benjamin Stickney was one of the leading citizens of St. Louis, and filled the positions of director in the St. Louis Gas-Light Company, the Missouri Pacific Railroad, and the St. Louis National Bank. He died on the 14th of November, 1876. After his retirement the house was reopened by J. Fogg & Co., Mr. Fogg having previously been associated with Theron Barnum in Barnums Hotel.

[Excerpt from "A History of St. Louis City and County, From the Earliest Periods to the Present Day: including Biographical Sketches of Representative Men. Philadelphia: L. H. Everts & Co., 1883). Written by J. Thomas Scharf. Volume II]

Planter House Hotel #1

"The first establishment to bear that name opened in 1817 in a frame trading post on the river-front, where is remained until 1840, when civic leaders saw the need to build a top-flight hotel that would be counted among the finest in the nation."

Planter House Hotel #2 (at Fourth and Pine)

"The building of the second Planter's House Hotel was financed through the investment of private citizens. Contributors to the venture selected Pierre Chouteau, James Lucas, John Kerr, and Peter Powell to represent them as trustees.

Begun in 1837 and designed by Henry Spence, the new 300-room, four-story hotel was located at Fourth and Pine Streets, removed from the hurly-burly and odor of the river-front. It had a classic, dignified exterior and shops and offices at the ground level. There was a huge main dining room, and three additional restaurants were associated with it. The grand ballroom featured decorative details copied from the Temple of Erectheus in Athens, Greece. The Planter's House Hotel was considered the finest in the West and was seen by civic leaders as a symbol of the new St. Louis. It became the gathering place for politicians and businessmen and was the byword for luxury and good service. A room cost $4.25 per person per day, and the rate included four sumptuous meals. The trustees leased the facility to various operators over the years for the then-considerable sum of $7,000 per month.

Landowners from both the north and the south appreciated the hospitality and brought their families to spend the winter. One evening in 1841, the menu offered an imposing array of foods including filet de boeuf, fried oysters, broiled grouse, saddle of antelope, and wild duck. Desserts included custard pudding and apple, plum, and pumpkin pies.

Famous visitors were often in residence. Jefferson Davis, Abraham Lincoln, Andrew Jackson, Henry Clay, U.S. Grant, and William F. Cody � among others � all signed the register at one time or another, and Charles Dickens stayed there during his American tour. Dickens, who was notably critical of this country- and of St. Louis, wrote favorably about the Planter's House.

"We went to a large hotel called the Planter's House, a building like an English hospital, with long passages and skylights above the room doors to allow for circulation of air," Dickens wrote. "There were many fine boarders in it and as many lights sparkled and glistened from the windows down into the street below when we drove up as if it had been illuminated on some occasion of rejoicing.

"It is an excellent house and the proprietors have the most bountiful notions of providing the creature with comforts. Dining alone with my wife in the room one day I counted fourteen dishes on the table at once."

The second Planter's House continued as the city's beacon of hospitality for many years until 1887, when a fire severely damaged the building and it was closed. The old building, called an architectural nightmare by some, was demolished in 1891 to make room for a new, even grander, Planter's House Hotel.

Planter House Hotel #3 (site of Boatmen's Tower)

The new building was financed in an unusual way. When St. Louis was a candidate for the Columbian Exposition, civic leaders secured pledges of $5 million, plus an additional $1 million for entertainment at the fair. When the Exposition was awarded to Chicago, the group decided to offer a Si million bonus to any corporation or individual who could and would build a first-class, fireproof hotel in the city.

The bonus attracted investors who chose the Fourth and Pine Street site and retained Isaac Taylor to design the hotel.

Taylor's original design was for an Italian Renaissance building, but his plans were modified to an adapted Renaissance style to permit the inclusion of some French Rococo Renaissance rooms, which were considered the last word in elegance.

The 400-room hotel was built in an inverted "E" shape to allow natural light to pour into every room. The first and second floors were built of Ohio stone and granite, while the upper stories were of light beige-colored brick trimmed with cut stone. Molded bricks were used around the principal entrances in the front.

The magnificent front portico, made of cast iron, featured Ionic columns. It was crowned by an elaborate cast-iron balustrade.

Inside, grandeur and elegance were the order of the day. The lobby rotunda measured 50 feet from north to south and 122 feet from east to west. Colored marble lined the walls to a height of ten feet. The 20- foot ceiling was decorated with medallions of choice heraldic design. A large grand staircase stood at one end, topped by a large bronze guardian lion. At the base, a pair of bronze, human-size sprites held lamps aloft on each of the newel posts.

The main restaurant was considered the most elegant room in the city. It had many Doric columns and was decorated in tones of Empire green and silver. The hotel offered other elegant public rooms � the ladies' dining room, a sumptuous Moorish room, and various meeting and banquet rooms were much admired.

The main bar was well-known to civic leaders, politicians, and gentleman visitors. The bar measured 45 by 47 feet and was designed in a semicircle. it was there that bartender Charles Dietrich invented a cool and delicious lime, lemon, and gin drink called a Tom Collins � named after a regular and favored customer. Dittrich followed the footsteps of a predecessor who, years earlier, had given the world the Planter's Punch to enjoy.

For all its elegance and history, the Planter's House did not thrive during World War I. The doors closed on its present, past, and future in 1922. The building was converted for use as offices and was called the Planter's Building until 1930. It was then renamed the Cotton Belt Building.

It was finally torn down in 1976 to make way for construction of the Boatmen's Tower.

[Excerpt from "St. Louis Lost - Uncovering the City�s Lost Architectural Treasures" by Mary Bartley. Virginia Publishing: St. Louis, MO. Published in 1994. ISBN 0-9631448-4-7

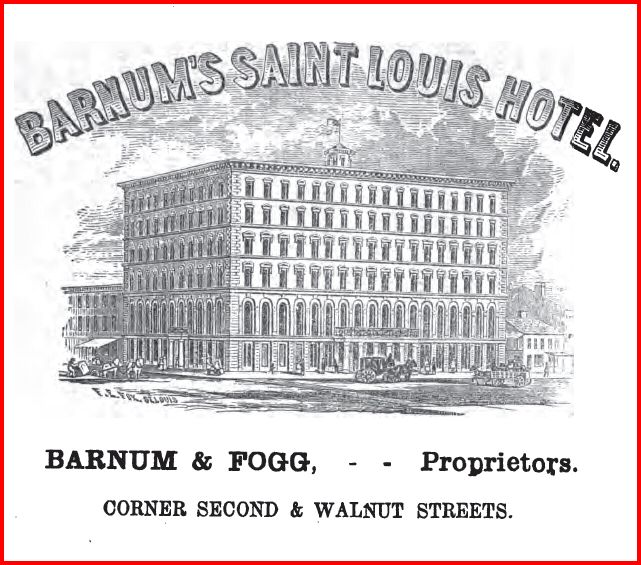

Barnum Hotel

Theron Barnum, the senior member of the firm, was born April 23,1803, in Addison County, Vt., and in 1808 moved with his father to Susquehanna County, Pa. There he worked on the farm, also getting such instruction as could be obtained in a country school. At the age of seventeen he began to teach school, and pursued that avocation for several years, in the mean time cultivating his mind in the advanced branches of English education. In 1824 he went to Wilkesbarre, Pa.,and filled the position of clerk in a store until 1827, when he removed to Baltimore at the request of his uncle, David Barnum, and became associated with him in the management of Barnums Hotel, then enjoying a well-deserved fame as one of the best hotels in the United States. He remained with his uncle in the capacity of confidential clerk, and became under his able instruction well versed in the art of conducting a first-class hotel. He then opened the Patapsco Hotel at Ellicotts Mills, fifteen miles from Baltimore, and the terminus of the first fifteen miles of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. While there, in 1832, he married Mary Lay Chadwick, daughter of Capt. Chadwick, of Lime, Conn., and captain of one of the large packets between New York and Liverpool. The fruit of this marriage was two sons, Freeman and Robert. In 1835 he removed to Philadelphia, and bought the Philadelphia Hotel on Arch Street, but having long thought of going to the West, he sold out in 1838, and determined to settle in St. Louis. On his way he was induced to stop at Terre Haute, Ind., where he opened the new Prairie House. He remained here only until 1840, becoming satisfied in the mean time that Terre Haute could never support the kind of hotel which he was desirous of establishing. In March, 1840, he removed to St. Louis, and rented the City Hotel; at Third and Vine Streets. This hotel was for a long time the favorite house of the public, and became the headquarters of the army officers residing in or visiting St. Louis. Among the distinguished officers who made the City Hotel their home were Gen. Gaines and Col. Qroghan. Mr. Benton also stopped here. Mr. Barnum managed the hotel for thirteen years, and in September, 1852, sold out. After a short retirement the present Barnum's Hotel was built for him by George R. Taylor, and for many years he had charge of it. During his supervision the Prince of Wales, George Peabody, William H. Seward, Abraham Lincoln, and many other distinguished persons stopped at it. In 1877 he took the Beaumont House, which he put in successful operation. He died there on the 17th of March, 1878, of pneumonia. Mr. Barnum was a cousin of P. T. Barnum, and seems, with the other prominent members of that family, to have followed his peculiar bent with a pertinacity and energy that deserved if it did not always achieve success. He filled at different times responsible positions, and was a director in the Home Mutual Insurance Company for thirty years.

[Excerpt from "A History of St. Louis City and County, From the Earliest Periods to the Present Day: including Biographical Sketches of Representative Men. Philadelphia: L. H. Everts & Co., 1883). Written by J. Thomas Scharf. Volume II]

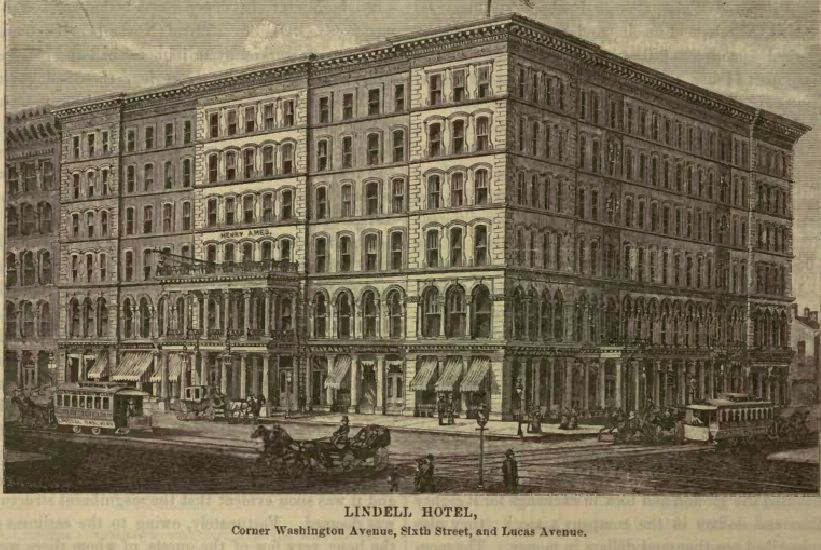

Lindell Hotel

About half-past eight o'clock on the night of the 30th of March, 1867, fire was discovered in the upper story of the hotel, and in a short time the flames burst through the roof and spread on all sides with great rapidity. The alarm was conveyed to the fire department, and the engines arrived without much delay. They were powerless, however, to stay the progress of the flames, the great height of the building rendering it impossible to throw water on the roof. In a short time the entire top of the hotel was on fire; the flames gradually worked downward, and it was soon evident that the magnificent structure was doomed. Fortunately, owing to the earliness of the hour, very few of the guests, of whom there were about four hundred, had retired. Those who were sick were carried out and conveyed to places of safety. As soon as it was known that the building could not be saved efforts were made to secure the stock in the different stores and the furniture and portable property of the hotel, much of which was saved. Within three hours the fire was at its height, the heat being so intense that water thrown upon the flames flew upward in sheets of steam. The firemen desisted from their fruitless efforts and devoted their attention to saving the surrounding buildings. About twelve o'clock the walls fell, and all that remained of one of the finest hotels in the world was a shapeless mass of ruins. The loss on the building was about nine hundred thousand dollars, and on the furniture between two hundred thousand and three hundred thousand dollars.

The destruction of the Lindell was regarded as a public calamity. Impromptu meetings of the citizens were held almost before the smoke had ceased ascending from the ruins to take measures for the erection of a new building, but it was not until five years had elapsed that these efforts were crowned with success. It became frequently, during this time, a question whether the new Lindell should be erected on the old site or at a point farther west on the same thoroughfare. The matter was finally determined by Mrs. Vincent Marmaduke (formerly Mrs. Henry Ames), who resolved to build on the spot made historical by the old Lindell. A company was formed consisting of Messrs. William Scudder, Levin II. Baker, and Charles Parsons, who engaged the well-known architect George I. Barnett to design the proposed building. About the 1st of September, 1872, the work was commenced by removing the rubbish from the old foundations for the purpose of constructing the new. The work was pushed forward without intermission through the untiring efforts of Messrs. Scudder and Barnett and the numerous contractors, and within two years from the breaking of ground the structure was completed. For two months more the process of fitting and furnishing went on, and on the 28th of September, 1874, the whole establishment in complete running order was thrown open to the public.

The exterior of the new building presents a very different aspect from the old one, being less ornate but much handsomer.

The first story is flush with the sidewalk, instead of having a basement elevating it several feet above the pavement. The principal front, as in the old building, is on Washington Avenue, with a frontage of one hundred and eighty-two feet, and a depth of two hundred and twenty-seven feet to Christy Avenue. The height of the building is one hundred and five feet, and the architecture is of the modern Italian school, the first story being of the Tuscan order and constructed of iron. The five upper stories of the facades on Washington Avenue and Sixth Street are composed of Warrensburg gray sandstone that hardens with age until it becomes almost as capable of resisting the elements as granite. The second story is composed in the principal compartments of Corinthian columns supporting semi-circular arches over the windows. The intermediate windows have semi-circular arches with caps, supported by carved trusses. This story is surmounted by a fine cornice, and the four upper stories are divided by five moulded water-tables. All the angles of the building are finished with heavy quoin-stones. There are three capacious stores on each side of the main entrance, and six equally so on Sixth Street. A striking feature of the front is a massive two-story portico immediately in front of the main entrance, forty-five feet wide, and projecting fifteen feet from the building, with six Tuscan columns below and six Corinthian columns above. Massive iron railings of unique designs inclose each floor. The ladies entrance on Sixth Street has also an elegant but smaller portico, one story high, with six columns. The whole building is crowned with a massive iron cornice eight feet high. On the first floor is a splendid ball or exchange, one hundred and fifty-five feet long, forty-one feet wide, and eighteen feet high. The ceiling is elegantly frescoed in intricate and tasteful designs and harmonious colors. The floor is laid in tessellated marble, and the walls are pleasantly tinted. Qn the west side of the exchange is the office, elegantly fitted up with all the modern appliances. Immediately west of the office is a spacious reading-room, comfortable and well lighted. Opposite the office is the grand staircase, an elaborate and stately structure. The walls and ceilings are elegantly frescoed, and a view upwards presents a most pleasing effect. There is not a dark room in the hotel, and the ventilation is excellent. There are two hundred and seventy guests rooms, which is about a score less than the old building had, but there are many more rooms devoted to public use, and the floor-room is much greater. Everything that forethought could devise for the comfort of the guest and the facilitating of business has been provided, and that, too, in the best possible manner. The proprietors of the Lindell were Messrs. Felt, Griswold, Clemmens & Co., being W. W. Felt, of the old Lindell; J. L. Griswold, formerly superintendent of the Ohio and Mississippi Railroad; H. H. Clemmens, formerly one of the proprietors of Congress Hall, Saratoga; and Charles Scudder. The chief architect was George I. Barnett; assistant architects, Furlong & Taylor; general carpenter and builder, Charles H. Birch.

The present proprietors of the Lindell Hotel are the members of the Lindell Hotel Association; Charles Scudder, president; Henry Ames, vice-president; William F. Haines, secretary. Mr, Scudder is a brother of Capt. John A. Scudder (of whom a full biographical sketch is given elsewhere), and, like his brother, is one of the most active and influential citizens of St. Louis. Maj. William F. Haines was born at Buffalo, N. Y., Nov. 5, 1829. He was the son of Samuel Haines, of Lancaster County, Pa., and his mother was formerly Miss Anna Lengeker, of the same county. At the age of sixteen William F. Haines served as ordinary seaman on the brig "Odd Fellow." After nearly a year "before the mast" he was employed in Robinsons banking-house, and at the age of seventeen was cashier of the Merchants National Bank of Erie County, N. Y. Subsequently young Haines returned to school until September, 1849, when he removed to St. Louis, where his first occupation was that of book-keeper in the commission house of David Tatum. In the spring of 1851 he accepted the position of chief clerk on the steamer "Josiah Lawrence," plying between St. Louis and New Orleans, and was identified with various river steamers as chief clerk and master until the opening of the civil war, when he entered the Confederate service as private in Capt. James Pritchards company, First Missouri Regiment. He was afterwards appointed quartermaster of the regiment, with the rank of captain, and after the promotion of Col. Bowen, of the First Missouri, to brigadier-general, Capt. Haines was made brigade quartermaster on his staff, with the rank of major. He participated in all of the engagements in which Gen. Bowens several commands took part, and was in Vicksburg during the siege.

On being exchanged, Maj. Haines was sent to serve with Gen. L. S. Baker, in North Carolina, where he remained until the close of the war. Gen. Bakers command being cut off from the main army of Gen. Joseph E. Johnston, Maj. Haines was sent to Raleigh to arrange terms of surrender with Gen. W. T. Sherman. Having previously known Gen. Sherman in St. Louis, Maj. Haines secured the same terms given to Gen. Lee, and was designated as paroling officer of Gen. Bakers command. After the war closed, Maj. Haines returned to St. Louis and resumed his river occupation, becoming captain of the steamer "Stonewall," plying between St. Louis and New Orleans. In December, 1865, he married Miss Abbie Kennerly, youngest daughter of Capt. George H. Kennerly, formerly of the United States army, and whose mother is a daughter of the late Col. Pierre Menard, of Kaskaskia, Ill. The fruits of this marriage were four daughters and three sons. Maj. Haines was for twelve years general freight agent of the Mississippi Valley Transportation Company, which position be held until February, 1882, when he became one of the proprietors of the Lindell, and of the Hotel St. Louis, at Lake Minnetonka, Minn.

[Excerpt from "A History of St. Louis City and County, From the Earliest Periods to the Present Day: including Biographical Sketches of Representative Men". Philadelphia: L. H. Everts & Co., 1883). Written by J. Thomas Scharf. Volume II]

Pacific Hotel

James Francis Geary, local reporter of the Leader, and Elihu Hays died on February 24th from injuries received at the fire, making the entire number of deaths twenty-one. A meeting of citizens to provide for the burial of the dead and the relief of the wounded was immediately called. Col. Thornton Grimsley presided, and committees were appointed to provide for the interments and to obtain subscriptions for the survivors. Twelve of the dead were buried in Bellefontaine Cemetery, their remains being followed to the grave by the largest procession ever seen in St. Louis. The survivors, so far as they could be discovered, were handsomely cared for and assisted.

[Excerpt from "A History of St. Louis City and County, From the Earliest Periods to the Present Day: including Biographical Sketches of Representative Men". Philadelphia: L. H. Everts & Co., 1883). Written by J. Thomas Scharf. Volume II]

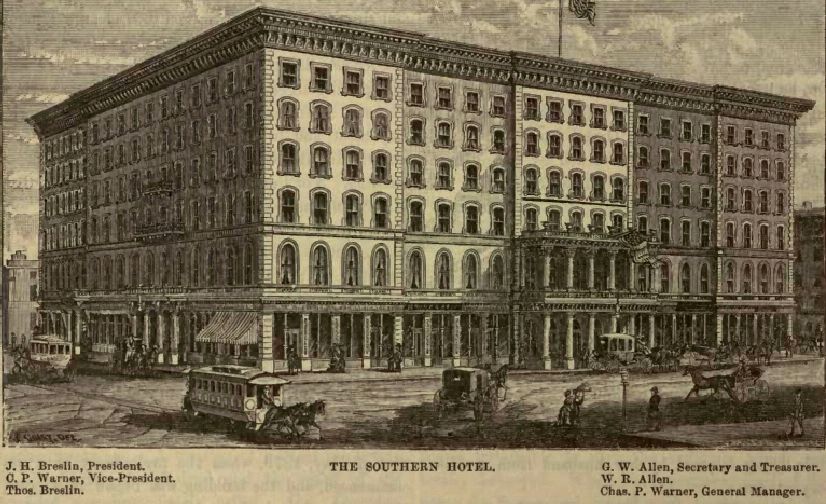

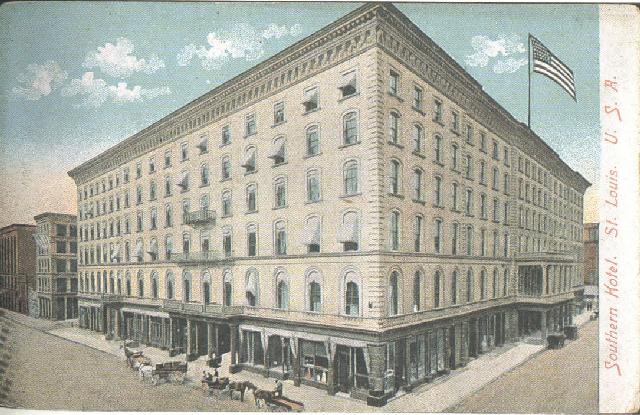

Southern Hotel

The hotel was destroyed by fire early on the morning of April 11, 1877. The fire was discovered at twenty minutes past one o'clock in the basement of the hotel. The inmates were aroused as far as possible, and an alarm was sounded through the agency of the district telegraph. This brought out the salvage department, but the key of the fire-alarm telegraph-box having been lost or mislaid, it was ten minutes before the city fire department could be notified. On the first call six engines and two hook-and-ladder companies responded, but, the fire gaining rapid headway, two subsequent alarms were sent in, calling out the entire department. To the natural progress of the flames was added the flood of gas from the large pipe used in supplying the hotel, and it was soon found impossible to save the building, which was totally destroyed. When the department reached the scene the flames had gained such headway that the efforts of the firemen were directed particularly to saving the lives of the inmates. Of these there were several hundred, including a number of female domestics, who slept on the sixth floor of the hotel. The fire was first discovered in the store-room, which was in the basement near the passenger elevator, and the flames, ascending through the elevator shaft, spread immediately over the two upper floors, and filled all of the halls and corridors above the ground-floor with dense smoke, which rendered escape a matter of the greatest difficulty. The loss of life was exclusively among the occupants of the fourth, fifth, and sixth floors, who, their means of escape being cut off by the fire, either fell or jumped into the streets and were killed. Many, however, were saved through the agency of the fire department and citizens by means of ladders, and there were scores of rare instances of heroism on the part of rescuers, whose efforts were rendered peculiarly dangerous owing to the height of the burning building and the inaccessibility of the upper floors.

The conflagration was made the subject of an investigation by the proper authorities, the jury consisting of John McNeil (foreman), Sylvester H. Laflin, Walter C. Carr, Jacob Tamm, Charles W. Irwin, and George Bain. Ninety-two witnesses were examined, and in rendering their verdict the jury said, "As to the cause of the fire, we have no testimony sufficient to base an opinion on, but from the dryness of the woodwork and the inflammable material in the storeroom, wine-room, and carpenter-shop, all situated in the basement of the hotel, it would have required only the slightest spark in a very few minutes, if not discovered, to have caused a fire of such magnitude as to be beyond ordinary control." The victims of the fire were George F. Gouley, of St. Louis, secretary of the Grand Lodge A. F. and A. M. of Missouri, who was killed by falling from a fourth-story window on the Walnut Street side.

Henry Hazen, of New Castle, Pa., assistant engineer Missouri Pacific Railroad, killed by falling from a third-story window.

Mrs. Abbie Moran, Mary Dolan, and Kate Reilly, all domestics employed in the hotel, killed by falling from a fifth-story window of the south wing.

Rev. A. R. Adams, vicar of the parish of Stockross, Berkshire, England, killed by falling from a fourth-story window on the Fourth Street side,

Mrs. Jennie Stewart, wife of W. S. Stewart, of St. Louis, killed by the breaking of an improvised rope while being lowered by her husband from a fifth-story window.

Charles A. Tiernan, a well-known St. Louis sporting man, killed while forcing his way into the burning hotel to rescue the inmates.

Andrew Einstinan, of Teiehmann & Co., St. Louis, killed by falling from an improvised rope while descending from the fifth floor at Fifth and Elm Streets.

H. J. Clark, formerly of North Adams, Mass., an ex-railway conductor, found in the ruins after the fire.

Mrs. Abbie E. Clark, wife of H. J. Clark, and child, found in the ruins after the fire.

In addition to the above, the body of an unknown man was found in the ruins, and William F. Munster, of England, committed suicide a few hours after escaping in safety from the hotel.

Two policemen reported that during the earlier progress of the fire, while engaged in rescuing people from the burning building, they heard two pistol-shots, and on entering the room where the reports came from saw the dead bodies of a man and woman. There were also several persons missing who were never successfully traced, but whose death at the time of the fire has never been clearly demonstrated.

The hotel building was owned by Robert Campbell, who estimated his loss at three hundred and seventy thousand four hundred and twenty dollars, which was ninety-two thousand dollars above the total insurance.

The blackened ruins and the crumbling walls remained a ghastly memento of this awful disaster for two years, when, through the untiring energy and perseverance of the prominent members of the Merchants Exchange and other leading business men and citizens, chief among whom was George Knapp, senior proprietor of the Missouri Republican, a project for rebuilding the hotel took definite shape, and was speedily urged to a successful termination. Hon. Thomas Allen assumed the leading part in the movement, and to him more than to any other person was due the erection of the present magnificent building. For the construction of the hotel building, Mr. Allen engaged Messrs. George I. Barnett and Isaac Taylor, architects, to carry out his plans, and selected his son George W. Allen as general superintendent of the whole work. The Southern Hotel occupies the block between Walnut and Elm, two hundred and twenty-six feet, and Fourth and Fifth Streets, two hundred and seventy-five feet, has three fronts of stone on Walnut, Fourth, and Fifth Streets, and is six stories high, with an additional basement as highly finished as any floor of the house. Mr. Allen obtained possession of the block on the 21st of May, 1879, when the preliminary work was commenced, and the building was begun in August, 1879. Mr. Allens first and most solicitous object was to erect a thorough fire-proof house from basement to roof. To this end he bent all his energies, and enlisted the ingenuity of the architects and builders. On the principle that a building is only as strong as its weakest part, he resolved that there should be no weak place, and was constantly on his guard against a flaw. Enough of the heaviest railroad iron to lay seven miles of track was used as support for the floors, which are laid on solid cement. Besides the interior brick walls necessary to give strength to the structure, the apartment partitions are of gypsum, sand, cement, and pulverized coke, with no particle of wood in them. The doors, window-frames, and other necessary wood-work are of gum, cypress, and ash, hard wood, and of the finest finish. Should fire occur in any of the rooms it would necessarily stop with the furniture and upholstery of the one room, as there is no chance of its eating through or crawling out. There is no exception to this thorough fire-proofing in any part of the building. The builders pronounce the Southern the most thoroughly fire-proof hotel structure in the world.

Among the additional features of special interest are two engines, basement fixtures, running machinery for elevators, electric light, and the latest improved smoke consuming furnaces in the basement and kitchen, which also make drafts for carrying off all impure air. There are three hundred and fifty rooms for guests, connected with the office by a system of electric bells, and there is hot and cold water throughout the house. The building is heated with steam, and, besides, there are fireplaces and grates in every room for coal or wood-fires. The public parlors are also thus supplied. There are three main stairways of iron and slate, extending from the ground-floor to the upper story, for the use of guests, and two iron stairways for servants. Besides these there are five hydraulic elevators, two for passengers and three for freight and other purposes. It will thus be seen the means for ingress and egress are abundant.

The rotunda hall, extending from Walnut to Elm Streets, is two hundred and twenty-six feet long and sixty feet wide ; the cross hall, from Fourth to Fifth Street, is two hundred and seventy-five feet long and twenty-six and a half feet wide, and the rotunda terminates in a skylight at the roof, the several floors being guarded by balusters. A terrace-garden on the roof over the grand dining-hall is ninety-eight by fifty-eight feet in extent, and safely guarded by an iron railing. The garden is laid out with paths and promenades, and flowers and shrubbery watered by fountains. The furniture was ordered and selected wholly by James H. Breslin and Robert M. Taylor, and the entire outfit, including carpets, drapery, silverware, etc., cost two hundred and twenty-five thousand dollars. On May 11, 1881, the Southern Hotel was formally opened with a ball and banquet. Hon. E. 0. Stanard, chairman of the committee of arrangements, introduced Hon. Thomas T. Crittenden, Governor of Missouri, who made a brief address. On the following day the new " Southall" began to receive guests. The first non-residents to register were Governor and Mrs. Crittenden. The entire block was owned by Thomas Allen.

The Southern is managed by the Southern Hotel Company, as follows : James H. Breslin, president; George W. Allen, secretary and treasurer ; Charles P. Warner, W. R. Allen, Thomas Breslin. Of these, James H. Breslin and Charles P. Warner were identified with the management of the old " Southern," and have a wide public acquaintance. The various departments are in charge of the following persons : W. M. Bates, general manager ; John E. Mulford, private office and head book-keeper ; E. V. Williams, cashier, late of Tift House, Buffalo, N. Y. ; M. W. Quinn, chief room clerk ; Charles E. Myers, room clerk, Tift House, Buffalo ; F. W. Lee, key clerk ; William A. Gilbert, key clerk ; William Patton, night clerk ; Horace M. Clark, steward. W. M. Bates, general manager, was placed in 1859 in a responsible position in the office of the famous St. Nicholas, New York, where he remained for years. Then he connected himself with the Ocean House, Newport, R. I., when lie subsequently became a partner in the business. In 1877 he leased Congress Hall, Saratoga Springs, under the firm-name of Bates, Rogers & Farnsworth, and since has been connected with the Fifth Avenue, New York, and the Ocean House, Newport, R. I.

[Excerpt from "A History of St. Louis City and County, From the Earliest Periods to the Present Day: including Biographical Sketches of Representative Men". Philadelphia: L. H. Everts & Co., 1883). Written by J. Thomas Scharf. Volume II]